A Closer Look at Delta Arithmetic

In their 1996 paper published in ACM Transactions on Database Systems, Ghandeharizadeh et al. defined a formal algebra around Deltas (the encoded difference between any two states of a system) in a relational database. Their definition is actually generic enough to apply to any system whose state can be represented as a set of tuples, which is why it is still used in contemporary research on database versioning, including those involving non-relational data models (Khurana et al. Storing and Analyzing Historical Graph Data at Scale). In order to support my deep dives into a couple of modern designs that use Delta Arithmetic for versioning graph databases, I will spend some time in this post laying down its foundations, clarifying a few under-explained points along the way.

Delta Arithmetic - The Ground Rules

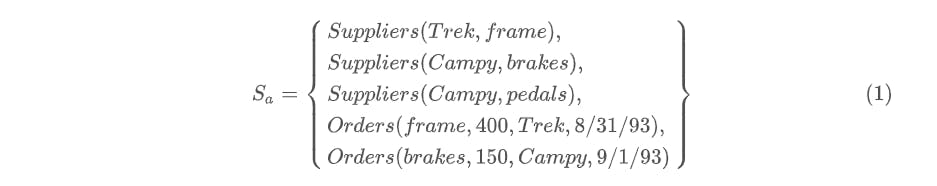

We start with a database containing the following relations or tables, for the fictional inventory management system of a bicycle manufacturer:

Suppliers- A list of vendors and the parts they sell,Orders- A record of orders placed to vendors, the parts and their quantities.

The contents of the two tables described above are shown below:

| Supplier | Part |

|---|---|

| Trek | frame |

| Campy | brakes |

| Trek | pedals |

| Part | Quantity | Supplier | Expected |

|---|---|---|---|

| frame | 400 | Trek | 8/31/93 |

| brakes | 150 | Campy | 9/1/93 |

Tuple Representation

Every record in the database is mapped to a classified tuple of the form \(RelName(field\_value_1, field\_value_2, ...)\). For example the first row in the Suppliers table is represented as \(Suppliers(Trek, frame)\) and the first row in the Orders table as \(Orders(frame, 400, Trek, 8/31/93)\). The order of values in the tuple is the same as the order of field definitions in the tables above. In this way, every row in every table in the database is mapped to a tuple. For this small database, we can write the entire initial state \(S_a\) as a set of tuples, as shown below:

It should be noted at this point that none of the tables above sport row identifiers or primary keys. However, since the algebraic definitions assume the pure relational model, every tuple is considered unique in itself, and cannot exist more than once anywhere in the database. This constraint is captured mathematically by the property of sets that require every element to be unique. Additionally, if one or more of the fields in the tuple constitute a key, then at most one tuple with a particular combination of values for those fields can exist at a time in the state set. For example, in the Orders table, if the fields (Part, Quantity, Supplier) fields constituted the key (a bad design in reality, but will suffice for this example), then every tuple in the set \(S_a\), apart from being unique in itself, must also be unique w.r.t to the sub-tuple formed by the above 3 fields.

Aside: The simplest way to remediate the uniqueness problem without enforcing uniqueness in tuples with semantic (business-relevant) fields is to add a field representing a dumb primary key. For example, a Order ID field in the orders table. This also permits repeating values for semantic sub-tuples in the Orders set.

Signed Atom

This is an expression of the form \(\pm\langle\text{RelName}\rangle\langle\text{Tuple}\rangle\) and corresponds to an insertion or deletion operation, depending on the \(+\) or the \(-\) prefix respectively. For example, \(+Suppliers(Shimano, brakes)\). This is the smallest unit of modification that can happen to the overall state set.

Aside: An update operation would require use of two atoms:

- One for deletion of the old value, and

- One for insertion of the new value.

As far as the set algebra used for delta arithmetic is concerned, the order of the above two operations does not matter, as long as the consistency constraints defined in the next section are met. Most databases, of course, allow atomic updates.

Since we're using sets to represent a pure relational model, a signed atom representing insertion of a tuple already present in the current state results in a No-Op. Similarly, a signed atom representing deletion of a non-existent tuple from a set also results in a No-Op.

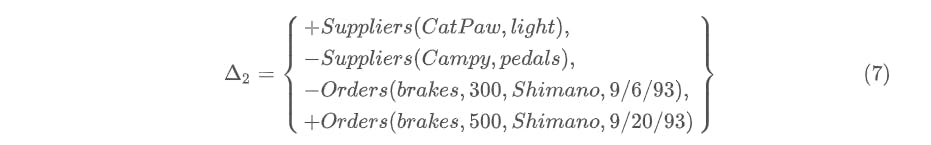

Delta

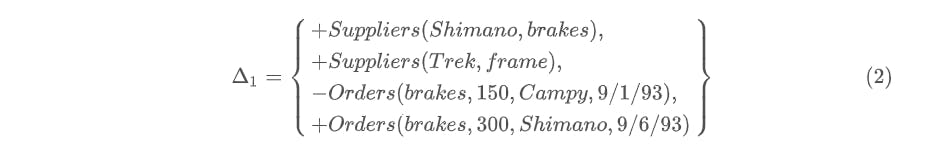

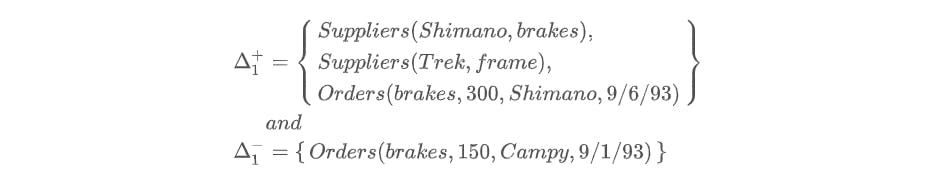

A delta is an unordered, finite set of signed atoms. For example,

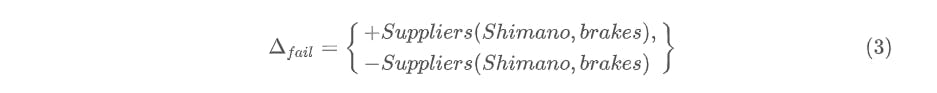

Consistent and Failed Deltas

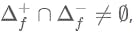

A delta is called consistent if it does not contain both positive and negative versions of the same atom. Otherwise, it is called an inconsistent, or failed delta. For example, the delta defined in (2) is a consistent delta, whereas a failed delta would look like:

Also, the delta being a set subject to the same uniqueness constraints imposed by keys (if present), we have the following: For a relation with two fields denoted by \(R[A, B]\), if \(A\) is the key and there exist two signed atoms \(+R[a, b]\) and \(+R[a, c]\) in a delta, then we must necessarily have \(b = c\) for the delta to be consistent (essentially collapsing them to a single signed atom).

Aside: One question that rose to my mind when I looked at (3) is why this should be disallowed. After all, the signed atoms within the delta are inverse operations of each other (insertion and deletion), and hence should just cancel each other out, resulting in a No-Op at worst. The paper does not directly address this question, though, as we shall see in a later section, this restriction is necessary to allow for delta operations to be safely applicable in any order (remember, the delta is an unordered set).

Delta Breakdown - Snapshot Fragments

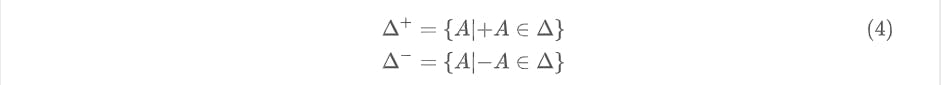

The paper defines the following relations for a consistent delta \(\Delta\):

The consistency requirement can now be expressed as:

For example, \(\Delta_1\) from (2) would be split into the following:

Although the paper doesn't explicitly name the definitions in (4), I will label them here as snapshot fragments. These represent the same type of elements in a set as the snapshot (tuples categorized by relation). The original delta, which represents events or operations, cannot be a direct algebraic operand along with the snapshot but its derivative snapshot fragments can.

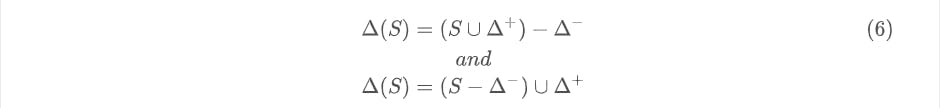

Now that we have defined delta components that can directly combine with the snapshot algebraically, we define the application of a delta \(\Delta\) to a snapshot \(S\) as the following equivalent functions:

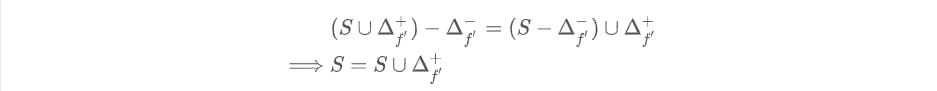

Why Inverse Signed Atoms Lead to a Failed Delta

A few sections earlier, we saw that a delta of the form illustrated in (3) is a failed delta, but did not elaborate on why it is so. Now that we have the commutative criterion of the delta function as described in (6), we can get a clearer picture.

We will examine two examples of failed deltas:

- One where the signed atoms represent an element already present in current state, and

- One where they represent a new element.

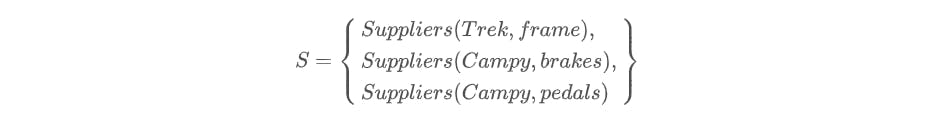

Say our current state has the following elements:

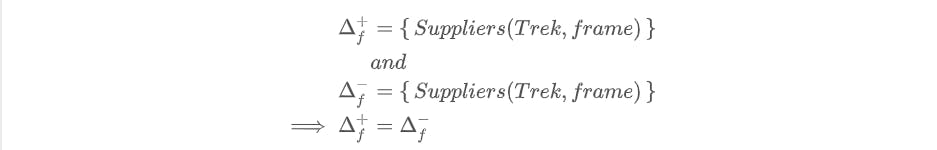

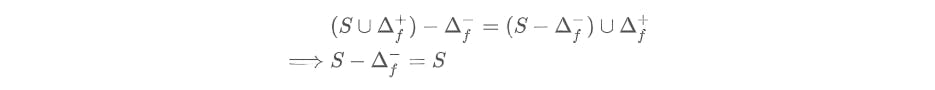

First let us consider case 1. Let \(\Delta_{f} = \left\{ \begin{array}{l} +Suppliers(Trek, frame), \\ -Suppliers(Trek, frame) \end{array} \right\}\).

Applying (6), we get:

We also note that

violating (5). To see if this delta still satisfies the commutative criterion of (6), we need:

violating (5). To see if this delta still satisfies the commutative criterion of (6), we need:

which is a contradiction.

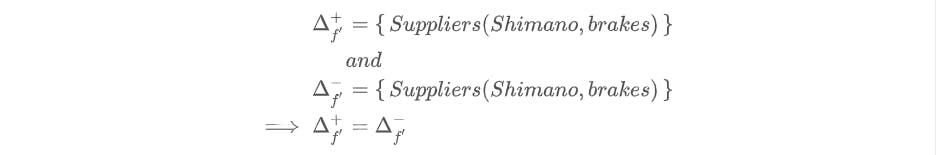

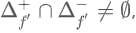

Now let us consider case 2. Let \(\Delta_{f'} = \left\{ \begin{array}{l} +Suppliers(Shimano, brakes), \\ -Suppliers(Shimano, brakes) \end{array} \right\}\).

Applying (6), we get:

We also note that

violating (5). To see if this delta still satisfies the commutative criterion of (6), we need:

violating (5). To see if this delta still satisfies the commutative criterion of (6), we need:

which is also a contradiction.

Therefore, we see that in order to satisfy the requirements in (6), we need to satisfy (5).

Delta Composition

Finally, I examine how the paper has formalized delta composition (or chaining) operations, thereby allowing us to apply at succession of deltas on a given state to arrive at the final state.

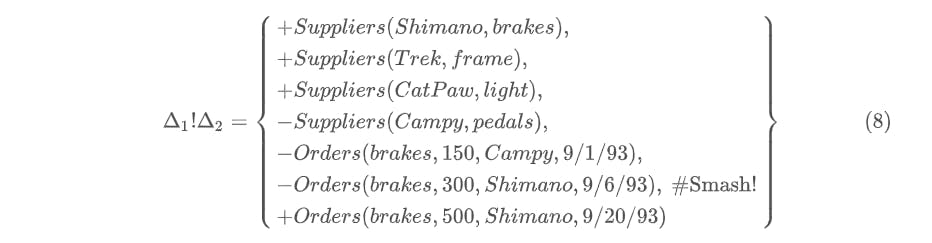

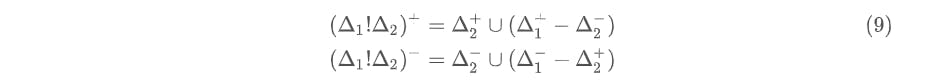

Smash Composition

One type of composition operation described is called a smash, denoted by \("!"\). This is the composition used by most active databases. Algebraically, a smash of two deltas is their union, with conflicts resolved in favour of the second argument. Given:

Then using (2) and (7) we get:

The formal definition for the smash operation is given by:

The reader is encouraged verify whether the above holds true for our example, using (2), (7), (4), and plugging into (9).

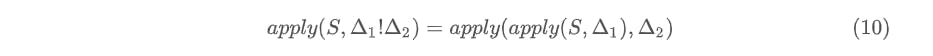

The most important characteristic of the smash composition is that it supports function composition, i.e.:

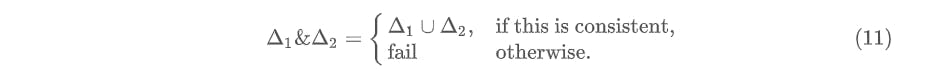

Merge Composition

The second type of composition defined by the paper is the merge. This is less common in real world databases, and hence is not examined in detail. The merge is denoted by \("\&"\) and its formal definition is given by:

Refer the paper for a slightly more detailed explanation of this.

Summary

The authors have used elementary set algebra to come up with some elegant mathematical formalizations for representing database changes over time. Though they have presumed the presence of a pure relational context, there is nothing exceptional being done at the set algebra level - all its rules are strictly followed. This opens up the possibility of using delta arithmetic to analyze any kind of database whose states can be represented as sets of tuples. As we shall see in a future post, this is exactly what Khurana et al.[^2] have done when designing their Temporal Graph Index.